By Marisa Silver

The difference for me between writing a short story and writing a novel is, I suspect, as different as working in watercolors is from painting with oils, or writing the concerto is from constructing the symphony. In each case, both forms are used to express the same thing – a narrative– but the way in which that story is told, and what the story ends up meaning for a reader is not only informed by content but by the form I choose to work in. In other words, deciding to write something in thirty pages or three hundred pages is not simply a choice about how to spend my time, or about how quickly I want to have the feeling of completion, but it is a decision about how best and most powerfully to convey my idea.

So, what’s different? The more obvious differences have to do with what a short story requires. For me, a short story is about compression. It is about choosing the very few actions, emotional beats, and bits of characterization that can suggest a whole universe. I always think of it as a kind of high wire act, because I have to be very careful that the images, the pieces of dialogue, the one or two details that describe a person accomplish enough to create a deep resonance. It is as if I want to make sure that every word says what it means and at the same time suggests other layers of meaning, so that even within the framework of a twenty or thirty page piece, an enormous amount of information and emotional range is conveyed.

A short story is very much about what is not said. For me, the choice of what to leave out, what not to say, is as important as what I do choose to say. A novel can take the time to describe a place, or a family history, or the deep interiority of a character. A short story can’t take that time, and yet, it has to suggest all these things or else the experience for a reader is not rich enough. So it is not that the novel can tell us more than the short story (although in overt ways, of course it can.) It is that a short story has to tell us as much of itself through its negative space as though the words that appear on paper.

Another strong difference for me is that a short story generally conveys an existential situation, a state of being, rather than a fully-fledged plot. Of course things “happen” within the pages of my short stories, but the plots tend to be smaller in scope. In my novels, the plots have to do more heavy lifting. They have to propel a reader through a longer reading experience, and so they have to have more complexity.

I’m often asked whether I want to turn a particular story into a novel. It’s a flattering question, because it is usually asked by a reader who is captivated by a set of characters. But the truth is, I never do want to do this. An idea appears to me as a short story, or it appears to me as a novel. I suppose that some ideas just feel that they need to be contained, that their power and effect will be most forceful if I express them using the tools of the short story. Other narrative notions have resonances that are like tentacles that reach out, ideas that lead to other ideas. These extenuating ideas circle around the central notion, but the central notion will not be complete, and will not reach its full potential, unless I take the time and space to explore all that richness that surrounds it in words.

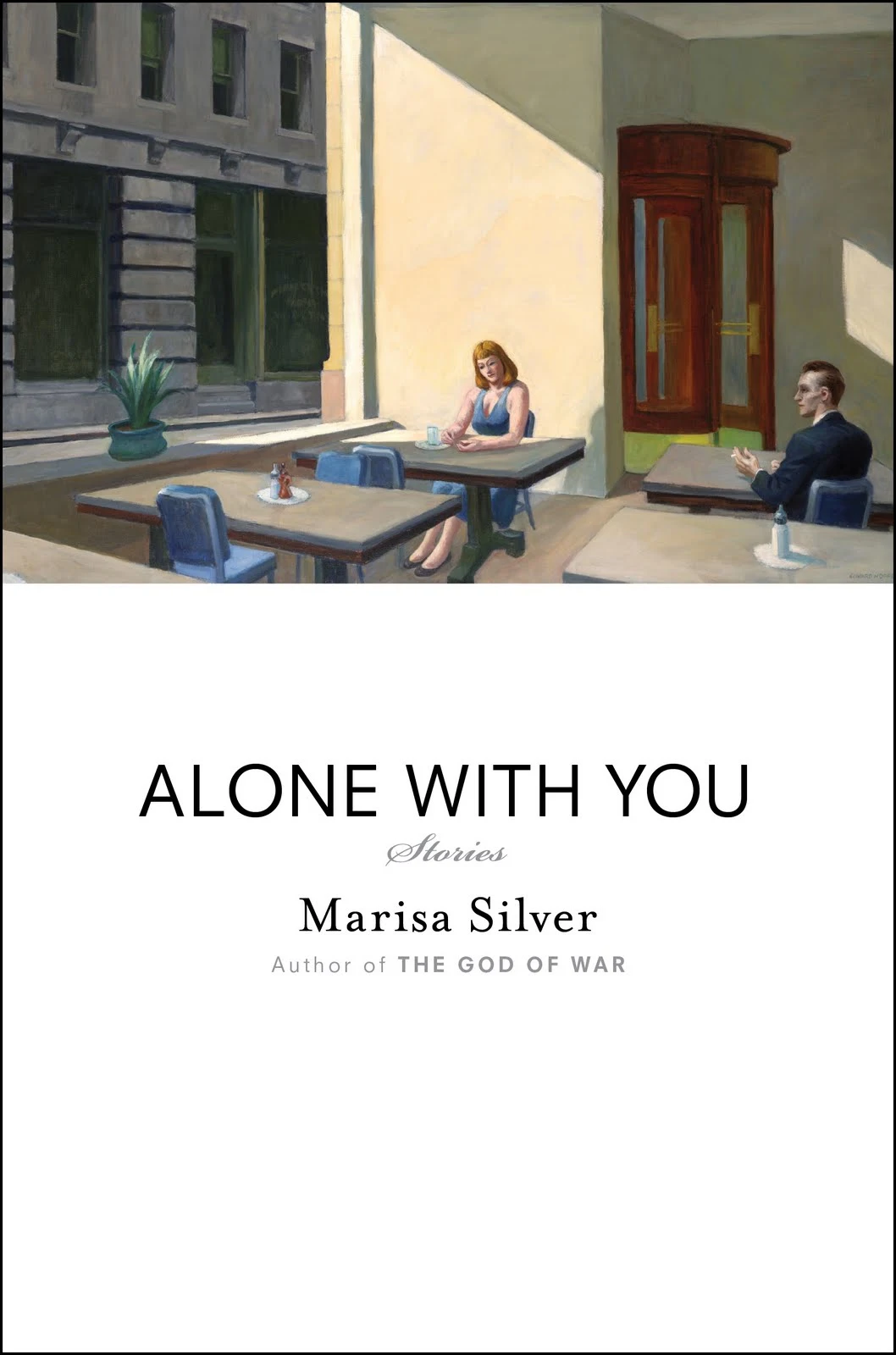

Marisa Silver is author of New York Times Notable Book, Babe in Paradise, No Direction Home, and The God of War, a finalist for The Los Angeles Time Book Prize and, a collection of stories, Alone With You.

Photo by Bader Howar

Interested in contributing a guest blog post of your own? Check out the guest blogger guidelines.